Donald Parkinson assesses the 2021 DSA Convention and imagines a path forward beyond its current political and strategic deadlock. Reading: Cliff Connolly.

In the modern Left, conventions, or to use the more classical term, congresses, tend to be places where organizations consolidate and confirm their internal political processes, rather than places where real political development occurs. Of course, some debate happens at conventions, and this debate does have an impact on the resolutions taken up and the decisions made, but pre-existing balances of forces and political trends tend to be decisive. This is especially true of the 2021 DSA Convention, held through a mix of Zoom video conferencing and Airtable voting forms, rather than actual face-to-face meetings among comrades. Little debate seemed to occur at all, with each resolution typically having three brief speakers for and against the proposal. Most of the actual deliberation and adjudication occurred online before the convention in the backroom channels of various caucuses, with the convention simply formalizing decisions already made.

If conventions are expressions of the deeper changes in an organization over time, what was expressed at this convention? To put it simply, DSA has taken steps back to the right after a leftward lurch at the last two conventions. A climate of fear and conservatism dominated the 2021 convention: fear of the socialist movement moving independently and standing on its own legs, and conservation of the status quo. This isn’t to say there were no positive developments; some excellent organizers were elected to the NPC, a political platform was adopted, and the body passed various structural changes that will improve the organization, while voting down others that would organizationally mutilate the org. But on the key question of moving towards class independence, this convention was a defeat for those of us who hoped to see DSA move towards becoming a real party of the working class.

The Terrain of the Convention

DSA’s 2019 Convention was defined by the theme of centralization vs decentralization. Factions like Build and Libertarian Socialist Caucus emphasized local chapters placing authority and funds in their own hands, often with a view of the national org itself as inherently compromised by reformism to the point where it would be better to make it utterly powerless. On the other side were Bread & Roses, “centralizers” who wanted to orient DSA behind a strategy of “class struggle elections” and a “rank and file strategy” in labor. This centralizing vs decentralizing dichotomy is a simplification, but it captures the overall dynamic at play. In the end, the centralizers won out.

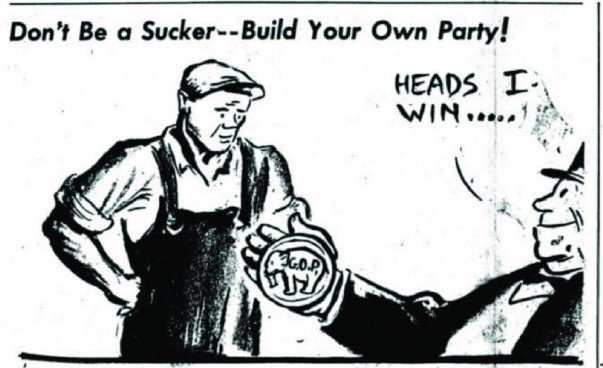

The 2021 Convention could be defined by a dichotomy of liquidationism1 vs class independence. On this front, DSA took a step back to where it was in 2017. Despite voting to ratify a political platform that in many ways was quite revolutionary and at odds with the politics of the DNC, the organization ensured that it would do as little as possible to actually pursue any practical measures to allow it to independently project these politics on a nationwide scale. To those on the far left, like the Trotskyist publication Left Voice, the convention justified publishing a sneering “told you so”, it was an excuse to bash DSA and assert that its confused relation to the Democrats and lack of class independence is inevitable due to the organizational genealogy of DSA itself. The article offered no real constructive ideas on how those in favor of a class independent electoral strategy in DSA can push against the rightward drift.

Second to the issue of class independence vs liquidationism was the issue of Internationalism. Shortly before the convention, a DSA liaison meeting with Venezuelan President Nicholas Maduro occurred, an initiative of the International Committee which is appointed by the elected National Political Committee (NPC). Before the trip the International Committee proposed a resolution to form connections with the Latin American left, which in light of the Venezuela trip was taken to mean more trips of the sort. The result was a proxy battle between a faction emphasizing support for anti-imperialist governments and a faction taking a “third campist” approach that social struggles from below should be supported regardless of the government they oppose, viewing alliances with parties in government as a betrayal of solidarity. These debates have continued long after the convention, now centering around the Chinese government and what DSA’s orientation towards it should be. It seems inevitable that the International Committee will continue to be a lightning rod for debate in DSA, with contesting visions of what socialist internationalism and anti-imperialism entails being the key issues. With the move away from Harrington-style Socialist International politics, the organization will have to find a serious vision of internationalism to replace the bankrupt one of the past.

The political alignments in DSA may seem contradictory at first. For example, the factions that take the hardest line of support for Pink Tide governments like Venezuela with the greatest emphasis on anti-imperialism, Collective Power Network (now defunct) and the Renewal slate for NPC also favor continuing work in the Democratic Party and totally abandoning the idea of a dirty break to create an independent socialist party. On the other hand, groups who favor the dirty break, like Bread and Roses (though they are somewhat timid about it – more on them later), Reform and Revolution and Tempest, were also the most opposed to building relationships with Pink Tide mass parties. Strident anti-imperialism is clearly in contradiction with the Democratic Party and DSA’s current leniency towards elected members who vote for imperialist agendas. Yet this contradiction was completely unacknowledged throughout the convention debates.

My own group, Marxist Unity Slate (which is currently transitioning towards a proper caucus formation) had three delegates who were official members and a decent amount of delegates who sympathized with our positions and resolutions. We did not expect any real kind of major victory. We are a small group only at the beginning of formation and saw the convention as a place to test how much sympathy existed for our positions. Our attempt to get an amendment to the platform that called for a more explicit break with the liberal constitutional order and its replacement with a democratic republic of the working class, including the dissolution in the US military in favor of a popular army, narrowly failed to receive enough signatures from DSA members to make it to the convention floor. Only one of our policy proposals, CB8,was debated. The amendment was an effort to move DSA closer to the principles of programmatic unity by making acceptance of the platform the basis of DSA membership. Sadly, the proposal did not pass, but received sizable minority support ( approximately 35%).

The greatest disappointment of the convention was not the failure of my own group to have the proposal it authored taken up. This was expected, although it did seem possible CB8 would be accepted. Rather it was the fact that resolutions which were to the right of ours while nonetheless pushing for a more aggressive attitude against the Democratic Party were also voted down. While DSA is still contested territory and worth engaging with, the majority of its members are seemingly comfortable with the way things are going in the org and reject any kind of changes in political strategy that will build an independent electoral apparatus that is actually accountable to the politics of DSA. The message was more of the same, rejecting any bold political vision that would challenge the status quo of the US political system.

Regressing Away from Class Independence

The best example of this rejection was the debate over Resolution 8, “Towards a Mass Party in the United States”, which as it stood was the typical boilerplate about the need to contest elections on the Democratic ballot line and make electoral politics the priority of the organization. The argument summarized can best be stated as follows: the United States has an electoral system that does not allow for traditional parties, defined as “private organizations with control over their membership rolls and ballot lines” but is instead based on “coalitions of national, state, and local party committees, affiliated organizations, donors, lawyers, consultants, and other operatives”. This is already a questionable statement. While the Democrats and Republicans are clearly not mass membership-based parties, they are best described as cartel parties, more in line with the parties of 17th Century Britain than the 19th Century mass parties. The Democratic Party is still a traditional party of some kind, and it is still a party where the top is able to discipline the organization to fall in line with the class fractions that it represents. It is not an empty vessel that we can use at will without consequences.

The resolution combines this analysis of political parties with the observation that the Republican Party represents the most reactionary wing of capital, while the Democrats have “the historical support of a multiracial working-class base.” The conclusion, then, is that our unique electoral system obligates us to run as Democrats while also building our own party, with no real strategy of how to actually transition from running as Democrats to walking on our own feet as our own party. Instead, the proposal merely states that we must “[oppose] the dominant corporate and neoliberal Democratic establishment”. As it stood, the resolution was a feckless restatement of the failed status quo strategy in the DSA, with no indication of actual antagonism against the Democrats.

Two amendments aimed to solve this problem, one from members of Bread and Roses and the other from the ex-Socialist Alternative caucus Reform and Revolution. The situation with Bread and Roses requires some explanation, and there was an internal divide over their amendment. The caucuses’ own membership voted on whether to endorse it with a split of 55% for and 45% against. When prominent leaders decided to pack their bags and leave the caucus or its leadership in response, it was decided to withhold endorsement of the amendment, which called for DSA to urge their candidates to “reject a strategy of capturing the capitalist controlled Democratic Party” and to build Democratic Socialist caucuses in legislative bodies. It aimed to give some teeth to the dirty break strategy, not nearly sufficient but at least a step above the existing resolution. The Reform and Revolution amendment called for candidates to be urged to uphold a socialist message about the Democratic Party (in other words opposition to it), a bare minimum,, but still more of a litmus test for endorsement than what was present in the original resolution.

Both amendments were voted down, with Eric Blanc, one of the original architects of the dirty break concept who has reneged on it recently, from Bread and Roses releasing an article shortly before it was voted on urging DSA members to “Focus on Scaling up Working-Class Power, Not Debating the Dirty Break”. Blanc argued that focusing on the dangers of cooptation by the Democratic Party overestimates the danger at hand and underestimates the gains we have won and can win. Blanc even goes as far as to say that “the vanguard of the working class, including its most militant unions, consistently support Democrats.” As a consequence, “dirty-break propagandism” will only serve to alienate this vanguard and hurt our ability to win electoral campaigns. It’s hard to imagine what kind of working class vanguard Blanc has in mind that is so loyal to the Democratic Party that they would refuse to vote for a candidate who talks about the need to break from that party and is fully loyal to a socialist organization.

Blanc’s arguments here are not those of the entirety of Bread and Roses, but they do show the danger of the caucus’s proposed dirty break strategy: the break is forever banished to a distant future, something that will happen one day when the conditions are correct. According to a comrade of mine, Blanc has said in an NYC DSA talk that the break will have to happen when a constitutional crisis happens, a do-nothing approach that conforms to the false stereotypes of Second International Marxism as passively waiting for revolution to occur. Rather than putting our own political agency at the center in fighting for the party we need, the party we need will fall from the sky when factors completely outside our control align. Until then we can only wait in a political limbo and build a progressive wing of the Democratic Party.

What would actually moving towards a break look like? Simply making minority proclamations about breaking from the Democrats will not do the job. The least we can do is to actually pass policies at all levels of DSA (and successfully implement them) that will hold candidates accountable to the platform and the organization’s elected leadership. This was the aim of the Marxist Unity Slate’s own Tribunes of the People resolution. We should of course go further. As Ben G has eloquently argued, we do need to actually run as independents, and this should be pushed for whenever possible. It is true there are genuine institutional barriers in our country to run such campaigns, and that in some states the only possible way to get on a ballot as a viable candidate is to run as a Democrat. If campaigns find themselves in this situation, they must not run as “entryists” in the Democratic Party, but “anti-Entryists” as Rosa Janis argued in an early Cosmonaut article. They would openly state that the only way they could get on the ballot was to run as a Democrat and that a new party is needed, fight to pass legislation that would weaken the two-party system, and caucus with other socialists rather than other Democrats. If the Democratic ballot line is truly only a ballot line, then candidates must treat it that way.

Until the next convention, there is little we can do to improve DSA’s endorsement policy at the national level. What we can do, however, is begin fighting at a local level to implement similar policies. Boston DSA is already leading the way by adopting a resolution similar to the Tribunes of the People proposal. By showing that these policies are viable and capable of being put into practice, we can challenge conservative assumptions about what is electorally possible, directly showing what an actual socialist electoral strategy would look like in practice. Through such initiatives, an actual bloc that can fight for real changes at the national level can emerge, having built local institutions that give legitimacy to the claim that our ideas are possible. While DSA at the national level may not want to act like a party, we can at least fight for our organization to act like a party at the local (as well as state) level and convince our organization through force of example.

The Struggle for Programmatic Unity

My own group’s attempt to make DSA act a bit more like a proper party that actually made it to be debated on the convention floor, CB8, was also voted down 340-640. By making acceptance of the platform (which was ratified at the convention the day before this constitution change was voted on) the condition of membership in the organization, rather than the vague “acceptance of the principles of democratic socialism”, CB8 was an attempt to make DSA organize itself around the principle of programmatic unity. Rather than making membership be based on a pure big-tent with no clear demarcations from the broader camp of progressives or on the other hand adherence to sectarian understanding of Marxism, we aimed to make membership hinge on the acceptance of a series of overall goals for the movement, some long term such as the establishment of a socialist society, and others more short term. While the content of the platform itself is not an ideal minimum-maximum program, it does contain much to admire. Some in the organization were opposed to the platform altogether, claiming it was “class reductionist”. This was driven by the most right-wing factions of DSA, North Star and Socialist Majority, the wings closest to the classic Harringtonian politics that we have been struggling to escape. It is no wonder then that they opposed a program that is very much at odds with the Democratic Party’s current politics.

Yet it was not simply these wings who voted against CB8. Some saw in it a plot to purge those who disagreed with the party line. Others thought there was not enough discussion of the platform and that it was simply too soon to make it binding in any way – perhaps in a few years this would change. An example of the typical opposition to this amendment was articulated by David Duhalde, who explained that “despite good-faith arguments to the contrary, [there were concerns that] platform items would be unfairly weaponized against DSA members and elected officials.” In an organization that embraces an “anything goes” approach to left politics and supports the most progressive talking Democrats in any election, this kind of response is predictable. But it is ultimately self-defeating. It leaves the platform utterly toothless, making it a document that is simply ratified and then forgotten if efforts are not made to bring attention to it. With the defeat of Bernie Sanders, DSA is now without direction, because it made no real contingency plan for his likely defeat. Ratifying a platform at the convention could have been a meaningful step for the organization post-Bernie, giving it a new sense of direction and purpose beyond day-to-day activism. It would have given members something to point recruits towards when they ask what our organization stands for. Yet, as of now, it is simply a document without a clear purpose or meaning beyond the fact it was voted on at convention by a majority of delegates.

It is perhaps true that if the DSA platform was given teeth it would be “weaponized against DSA members and elected officials” as Duhalde suggests. Imagine AOC being grilled by the press about why her organization wants to exit NATO or establish social ownership of all major industries – would she stand by DSA or throw us under the bus? What message would it send the public, and what message would it send to DSA members? Given that her membership would be contingent on acceptance of the platform, a situation like this would force a serious conversation in the organization about electoral discipline, what it means for candidates to be a part of our movement, and what it actually means to be a socialist in this country. The right-wing sections of DSA are terrified of this because it would force the organization to reckon with its contradictions, contradictions it is far too comfortable with.

Since no organizational amendments were made to give the platform any real meaning, it is up to members of the organization to do it through their own activities. DSA chapters should hold meetings to discuss the platform, both its positives and negatives, as well as find ways to connect the work of their chapters to it. DSA electeds should be given the platform and meetings should be held with them to strategize how to relate their work to its content. When DSA electeds make public statements and vote contrary to the platform it should be cited, if only to make clear to the organization that their representatives are acting contrary to the goals of the organization as ratified by its convention. This has already happened; in response to AOC’s “present” vote and Jamaal Bowman’s “yes” vote on funding the Iron Dome the DSA Twitter account pointed to its platform, mentioning that it “proudly states continued support for and involvement with the Palestinian-led BDS movement & efforts to eliminate U.S. military aid to Israel.” The statement made it clear the vote was “disappointing” but then blamed it on a failure to “build enough working-class power to ensure that votes like this can never happen again”, essentially excusing the vote as a product of external circumstances. Despite its flaws, the statement did point to the platform as the real expression of DSAs politics against the actions of its endorsed candidate. In the future, less compromising statements should be made.

Controversy Over International Questions

Another key dividing line at the convention was the issue of internationalism. These controversies have continued to be divisive in the months following the convention, especially around the correct orientation towards China. The central item was R14, which pledged DSA to apply to join the Foro de São Paulo (FSP). FSP is essentially a conference of different leftist parties in Latin America, with multiple different member parties from many nations. Prominent member parties include the Cuban Communist Party, Venezuela’s PSUV, and Brazil’s Workers Party. Based on the discourse around the FSP and R14 you would think it was a Comintern type body that required one to monolithically agree with all the affiliated parties.

This is not the case at all. For example, the Venezuelan Communist Party, currently in opposition to the PSUV, is also represented. Clearly, one can be a member of the FSP and have disagreements with member parties, as the organization is, as suggested by its name, a forum, not an organization that entails following a centrally decided political line. This didn’t prevent a variety of third campists in the DSA from presenting the issue as essentially one of whether you were personally loyal to the government of Nicholas Maduro. This was of course compounded by the fact that some of the people pushing R14 the hardest had met with Maduro himself and said positive things about his government, something that to the opponents of R14 was tantamount to a betrayal of true socialist internationalism.

Arguments against R14 in the convention slack often seemed to be more about the people behind the resolution and the recent trip to Venezuela than about the substance of the resolution itself. People were posting pictures of militarized Venezuelan police saying a “a yes vote on R14 is a vote for this” and talking about the need to “oppose all dictators.” More substantive arguments could be found in documents released by various caucuses in the leadup to the convention. Jared Abbot’s article in The Call made a point of the fact that the FSP has refused to condemn “the Maduro government’s abuses of political and civil rights” while members, including Maduro himself, have urged the forum to actively support governments like his own and Daniel Ortega’s in Nicaragua. He also noted that certain member parties have formed their own alternative to the FSP, the Grupo de Puebla, absent the likes of Maduro, Ortega, and Cuban president Miguel Díaz-Canel. Yet the most prominent political leaders involved in this effort are hardly politically perfect either; one example is former Brazilian president Dilma Roussef, who oversaw austerity measures while in office.

More examples of the third campist perspective in opposition to R14 could be found in articles by the Tempest Collective. One authored by Promise Li accused the backers of R14, associated with the (now defunct) Collective Power Network and Renewal slate, of using the resolution to push their politics of “soft campism” onto DSA as a whole. Another by Natalia Tylim used the specter of the Venezuela trip as an example of more things to come if the resolution was to pass, pointing to a statement by Venezuelan Voices. Their arguments essentially boiled down to claiming that R14 was a proxy battle over the issue of campism, and that allowing it to pass would tie DSA to a politics of uncritically supporting left-wing governments against social movements in opposition to them.

Beyond membership in the FSP, the main aspect of R14 that the third campists took issue with was the language of “mass parties” in sentences like “International Committee will also continue efforts to establish relationships with mass Parties of the Latin American left”. This talk of “mass parties”, in conjunction with the personal politics of those backing the resolution as well as the controversy around the FSP turned the debate around R14 into a political proxy battle over the proper approach to internationalism. The actual strategic issue at stake, of whether DSA should apply to join the FSP and build relationships with various mass parties in Latin America, was lost. My own take on this issue is that joining the FSP would be a positive move for DSA, as our movement is far less advanced in its organizational skills and capacity than many of the member parties and has much to learn by forming relationships with these organizations and even doing exchange programs with them. Various mass parties in Latin America have much to teach us even if their politics are imperfect, and learning from them does not have to be a total endorsement of all of their politics.

The language around “mass parties” in the resolution is perhaps its biggest flaw, but it was not enough of a poison pill to prevent me from supporting it. Its problem is that it assumes we should prioritize who we form relationships with purely based on size instead of first communicating and investigating the political situation in various countries and making decisions based on these investigations. Many if not most countries with parties represented in the FSP have multiple parties involved and making preordained judgments on which we can learn the most from based on numbers alone seems mistaken. On the other hand, the third campist faction takes up a moralistic standard of “guilt by association” where mere membership in FSP would mean sharing a platform with various “authoritarian” parties and governments, thereby tainting DSA by proximity.

Recent events have given the Third Campist critics of R14 a moment of validation. In September, the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions (HKCTU) disbanded under pressure from the Beijing-backed leadership of Hong Kong. The DSA International Committee had an internal debate over whether to sign a joint statement condemning the role of the Chinese government in the dissolution of the union, deciding against signing through a majority vote. One side argued that this was implicit support for union busting, while the other said that the International Committee has no business commenting on the affairs of other countries’ labor disputes – a bizarre position for a committee whose aim is to make connections with the labor movements of other countries. Others correctly pointed out that the HKCTU has received funding from the CIA-backed National Endowment of Democracy, something admitted in Promise Li’s own article on the topic. All nuance was lost in a fraught online debate, where one was either an uncritical shill for the CCP or a dupe for US imperialism’s efforts of subversion.

Perhaps a compromise could have been reached, where the IC would release its own statement clarifying its opposition to the NGO arms of US imperialism subverting civil society in other countries while condemning the crackdown on labor organizations in Hong Kong. Yet the politics of both vulgar anti-imperialism and third campism make little room for such nuance. Third campists tend to tail every semi-popular democracy movement as a spontaneous outburst of popular activity that might just lead to a flowering of socialism from below regardless of their actual politics and leadership, most explicitly seen with the praise of the recent #SOSCuba protests that came from much of this tendency. On the other hand, vulgar anti-imperialism is a different type of tailism, where the object of tailism is not social movements, but the governments of whatever country has an antagonistic relationship to the US at any given moment.

Moving forward, a genuinely communist approach to internationalism must reject both of these dualities in favor of a genuinely class independent and revolutionary defeatist perspective. Such a perspective would comprehend that the main enemy is at home, that our priority is the defeat of our own country’s imperialist machinations and that the USA and imperialized countries like Venezuela are not equivalent threats to the people of the world. Yet it would also refuse to fall into vulgar geopolitics that makes the class struggle internal to various countries invisible. This is a difficult needle to thread, and can not be solved with simple slogans and mechanical schemas. What is needed going forward is a concrete analysis of any given situation that looks at the whole balance of geopolitical and class forces at play and a principled application of Marxist political principles. The current terrain of the debate makes such an approach difficult.

Labor Strategy, or Lack Thereof

While debates around electoral politics and internationalism were prominent issues, discussion around labor strategy was in short supply. This seems like a huge oversight at the moment of writing, as strike activity in the United States has been on the rise. Resolution 5 was focused on the issue of labor strategy, but managed to say as little as possible on the issue. It was not so much that the resolution was objectionable than that it seemed to take no real stance on the issue of labor strategy. The labor strategy question at the 2019 convention was defined by a debate between Collective Power Network’s “organize the unorganized” strategy and Bread and Roses’ signature “rank and file strategy”. While both resolutions ended up passing, leading to a similar kind of non-commitment to one approach prioritized over the other, there was at least some serious debate over the issue of labor strategy. At this convention, the passed resolution was seemingly designed to satisfy everyone as much as possible, while satisfying no faction fully. Support for working in existing unions and support reform efforts within these unions was affirmed, as was the need to engage workers outside the existing union movement. It simply affirmed what DSA has already resolved to do or recognized existing work that is already happening, like the Emergency Workers Organizing Committee and campaigning for the PRO Act.

The only debate that occurred over Resolution 5 was related to a proposed amendment that was authored by members of Socialist Alternative (SAlt). The aim of the amendment was to add in language that would increase hostility to the existing labor bureaucracy, stating

The main barrier to this is the majority of the existing labor leadership who run their unions in a top-down fashion with little involvement of the rank-and-file, accept far too many compromises and concessions, are unwilling to lead militant struggle, and give cover and support to the Democratic establishment. Given this approach they will also act as a major barrier to organizing new unions in previously unorganized workplaces and industries.

The amendment also mentioned that reform leaders in unions can also act as a conservative force and ended by pointing to the need for the union movement to have independence from the Democratic Party. While I am skeptical that the existing labor bureaucrats are the main barrier to the rise of the union movement, they are certainly at the very least an existing barrier that the socialist movement must be willing to fight against. It is also undeniable that the unions need actual socialist political leadership, not a patron-client relationship with the Democratic Party, if they are going to truly organize the masses of workers in a struggle against capitalism. The amendment was, of course, voted down, with much talk about how the fact it was written by a Trotskyist organization, SAlt, as if this was reason enough to vote against it.

Most disturbing, however, were arguments that amounted to defenses of the union bureaucracy, refusing to see them as a potential enemy that could hurt the socialist movement as it strives to merge with the union movement. Funnily enough, in my view, SAlt, despite my massive disagreements with their politics and methods of organization, has been practically vindicated by its recent work in the Western Washington Carpenters strike, which came into conflict with the union bureaucracy when union leaders tried to close down picketing against the wishes of rank-and-file members who found support from SAlt members. Regardless of how one feels about the politics of SAlt, one cannot fault them for their position on the labor bureaucracy nor condemn their work in this particular strike.

If DSA is going to seriously build a socialist movement in the United States, it needs to take the challenges of the labor bureaucracy seriously and commit to a labor strategy that can give political leadership and purpose to the labor movement. The strike wave taking off right now in many instances beyond Washington shows workers clashing with union bureaucrats who aim to hold their struggles back. Will socialists be able to step up and provide an alternative to the current misleadership? As of now, despite the encouraging militancy we are witnessing, the socialist movement is in no real position to do so. We are politically confused and dependent on our enemies, not even aware of who they are in many cases.

Onwards

So what is the way forward? For one, despite how frustrating the DSAs current political trajectory may be, it is still the place where committed Marxists need to be working. DSA may have its bureaucratic deformations and cultural problems, but it is still nonetheless a muchmore democratic organization than the sects and many reformist parties in other countries. The National Political Committee is elected by delegates who are directly elected by their chapters according to proportional representation. While it is a shame that measures that would have further democratized DSA, like holding all elections with Single Transferable Vote were voted down, the organization is much more democratic than others, even if major improvements can be made. We can still openly organize caucuses and factions, meaning that we can openly make the case for our minority positions to the membership at large and convince a majority of the organization. Unless a hysteria about “Trot entryists” takes over the organization and there is a clamp down on anyone suspected of being such, we have an open forum for our ideas.

What we need to do, however, is prove that our ideas work in practice. Writing articles, proposals and petitions is important but not enough. We have to show in our chapters’ day-to-day work what actual Marxist politics looks like and demonstrate what a principled electoral strategy can accomplish. This can mean building the structures and political cultures that can hold candidates accountable as well as running more militant and independent agitational campaigns to test the waters, find areas of support, and then build on them. Tenant organization2 and housing campaigns are another area of struggle that DSA can build and expand on, strengthening its ties to working-class neighborhoods and creating the foundations for district-level organizations. Labor work must be elevated so that we provide more than passive assistance to existing union struggles: we must actively fight for the hegemony of socialism in the labor movement. The structure of DSA creates the potential for us to put our ideas into practice at a local level, although in a very limited way. But it is a necessary step for convincing our fellow comrades that our ideas are feasible on the national level.

This local work must of course be coupled with a bold vision for the national organization. Marxists for class independence in DSA need to collaborate across caucus lines in a united front of sorts to fight for the kinds of changes that we need in the organization as a whole. DSA needs more open discussions on strategy and politics. One thing that was so frustrating about the convention was the incapacity for so many people to have real political debate. Instead, procedural and personal drama served as proxies for open and honest discussion about politics. We can fight against this toxic culture by setting an example and hosting open and frank dialogues among different factions. Through such dialogue, we can achieve a greater clarity about real political differences as well as the more important commonalities that are often lost in the heat of online polemics. After all, we are all comrades, despite whatever factional disputes we have with each other, united by the common bond of the socialist movement.

The times call for bold experimentation, not conservative caution. Applying Marxism creatively in these times will need a heroic vision of revolution in the USA and beyond. DSA is currently lost, set adrift at sea with no direction now that the Sanders campaign has failed. The Sanders vision, for better or for worse, held DSA together in the past years. Now we need to rely on ourselves for a vision, and it is my hope that myself, my comrades from the Marxist Unity Slate, and all of our supporters can help develop such a vision. We cannot cede any ground to those who say that we must wait for some far off day in the future to begin forming a party. We become a party by acting like one. It is time for us to create something bold and new in US politics instead of bowing to the status quo under the Biden presidency and pleading for minor concessions. Despite our weaknesses, our organization has attracted tens of thousands to join us in the name of socialism. Now it is our job to create a movement worthy of that name.

- By liquidationism, we mean the abandonment of the task of building up the forces of the proletariat as a hegemonic class with its own program and organization.

- Sadly a resolution backed by the Communist Caucus that would have poured resources into tenant organizing under the banner of the Autonomous Tenant Union Network was voted down.