Latest

Review

Building Epistemic Capacity: A Review of "Notes Toward a Digital Workers’ Inquiry"

Latest Cosmopod

We discuss Scandinavian Social Democracy from its origins to the present

Book Reviews

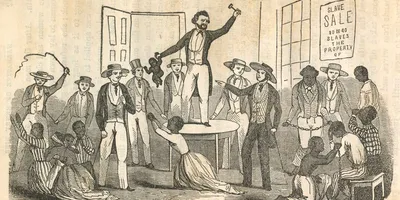

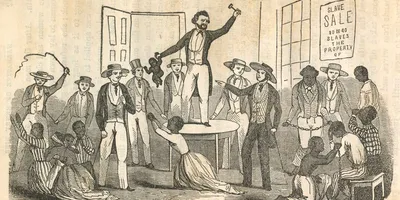

Process and Totality: A Review of David McNally's 'Slavery and Capitalism'

David McNally's Slavery and Capitalism: A New Marxist History offers a necessary corrective to the New History of Capitalism (NHC) group by embracing Marxism's revolutionary commitments, argues Julian Assele.

Your letters

Letter: On "Modern Industry and the Prospects for Socialism"

March 2, 2026

“Dear Editors,I read ‘Modern Industry and Prospects for Socialism’ by Dónal Ó Coisdealbha with great interest. The TPS (Toyota Production System) is indeed one of the greatest organizational …”

Letter: Truth From Facts

February 20, 2026

“Reading Ted Reese’s response to my criticisms of his recent Cosmonaut article, I found that much of my warnings about the limits of pure empirical analysis went unheeded. …”

Letter: Communist Strategy or Eternal Tailism? Reply to A Chinese University Student

February 12, 2026

“I write this letter as a youth from Portugal, who has been very much involved in the kinds of disputes discussed in the recent reply to Donald Parkinson's …”